My own, more recent, family history didn't paint a much brighter picture either. All of my grandparents were dirt-poor as children. Apart from one grandfather, all of them lost siblings while growing up. They had six years in school tops, spent part of their teenage years in cellars during WW 2 hiding from bombs and Russian soldiers, then started their families in the darkest period of the communist dictatorship. My parents' lives, growing up in the sixties and seventies, were incomparably better. And I and my generation had it the best so far.

So it was baffling to find out that others didn't share my opinion. A cousin of mine was a devout Catholic and very much into medieval history, so for her, the Middle Ages rocked. It was understandable, in a way. But I also recall a conversation that happened around 11th or 12th grade. I don't remember how we came to the topic, but an otherwise very smart, though probably a bit naive, boy argued that peasants in the olden times must have had a much better life than we. They didn't need to hurry anywhere, had a great community, and were able to enjoy small things in life. Well, I thought, since they buried a third of their children, had not much to eat, and were brutally exploited, they'd better enjoy the small things they had. There was a couple of similar conversations in the following years. Not too many, but all reliably similar to make me feel rather lonely with my worldview.

Things are going well...

Much later, around 3-4 years ago, I came across Steven Pinker's books, in which he demonstrates the decline in violence through the ages, and the progress humanity has achieved in almost every part of life that counts. Life expectancy, security, material well-being, education, freedom, tolerance, etc. It is a very long list. Pinker's work has been either a massive boost to my confirmation bias, or just a welcome vindication of my default worldview.

Around the age of 23, when I started reading newspapers, my view changed a bit. I still thought that from a historical perspective, life today was great - although not everywhere -, but I also had the impression that a day will come when it will be viewed as a golden era - that is, the good times won't last forever. Not because the trends showed a downward trajectory, more like the opposite, but there are ups and downs in everything.

...too well

The point I want to make with this long-winded rambling is that things are really much better today than they used to be. Having done so, now I can present the central thesis of the post: this state of affairs has some unforeseen and negative consequences. Our life has become so safe and comfortable that we can afford to be unserious. Not only in the political sphere, but in the general social realm.

It's been demonstrated in plain view by the ubiquitous attitude towards public safety and the well-being of others during the recent pandemic. Many people who could work from home, watch Netflix 24/7, and in general were not very affected by the pandemic, when facing some mild inconveniences (like the requirement of vaccination for entering restaurants and theatres), cried immediately tyrannies. The obligatory mask-wearing on public transport was "unbearable oppression". Vaccine certificates are the proof of a "dictatorship". Everything was about "my rights" and no mention of "my responsibilities" towards others. Perhaps the restrictions were overdone. But those who think that they now live under tyranny have no idea whatsoever what real tyrannies look like.

Back to politics, when Boris Johnson became the mayor of London back in 2008, I joked that the English are doing so well that they can afford to choose a clown as the mayor of their capital. At that time, I meant "clown" as more of a compliment. I didn't know anything about BoJo but he seemed like a cool guy.

On more recent events, I never bought into the story that the voters for Brexit and Donald Trump were the losers of globalization who felt that the "elite" is despising them. I thought both disasters were brought about by people who were simply bored and wanted entertainment. Practically no one starves today in the UK or in the States. No child is without a roof over her head. No one is facing religious persecution, everyone has access to education. No one seems to remember why the European integration started (spoiler alert, the Second World War). We live a pampered life, where the fiercest battles we can find are fought in Brussels, the House of Commons, and in the US Senate, and it's boring.

Politics used to be about material things because just two generations ago material things were of life and death importance. Today, politics is mostly about identity and feelings. People can make incredibly stupid decisions at the polling booth and nothing really bad will happen. And when the lower level desires of the Maslow pyramid are satisfied, our attention turns elsewhere. We want entertainment and to feel important, righteous, and smart.

I heard recently a historian explaining how well Hitler understood the underlying principle. Promising fight and glory, even hardships for the noble cause, captures people's hearts and imaginations more than "gradual change", "material prosperity", "steady improvement", "insightful debates", etc. The latter ones are what democracies should be about.

The infantilization on the Left

Being unserious manifested itself in different ways on the two ends of the political spectrum. Many on the left, feeling disappointed that the great battles for liberal ideas happened before they were born, decided to pretend that we live in the most homophobic, misogynistic, racist world, so they can feel good about themselves by fighting against it. In reality, no human in history ever lived in a place where it was better to be a woman, homosexual, or brown-skinned than the present, in the West. It's not that the wokes remind us that there is still much to do to lift up minorities. Many of them say with full seriousness that so far, there has been no progress at all.

... and the Right

On the right end, people started to fantasize about non-existent enemies (hordes of Muslim migrants in Hungary, power-hungry, faceless bureaucrats in Brussels, godless liberals destroying the nation in the US), and to wax lyrical about older, better, more God-fearing times of national greatness and their strong, wise leaders. Paranoia about international philanthropists, like George Soros, was always present, but now, when there was no Cold War to fill people's hearts with real dread, it has grown a hundredfold.

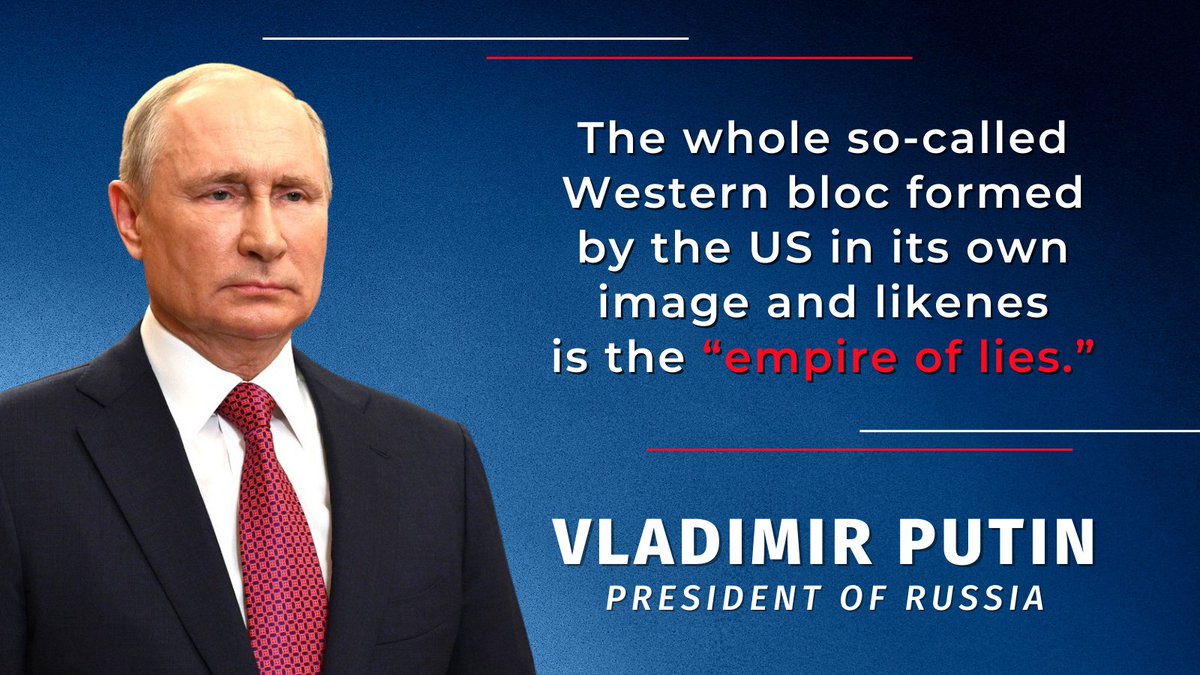

It is fascinating that it doesn't matter how much a leader steals openly, trashes democratic norms, or even orders the murder of journalists and political opponents, he only needs to say: "I stand for Christian/traditional values", to get an out-of-jail card from religious right-wingers of otherwise democratic affiliations and high education. The majority of American public intellectuals on the Right, after getting past the mandatory throat clearing ("yes, Orban is overstepping the legal boundaries, his media-handling is heavy-handed, blah-blah..."), will continue on expressing their admiration for the kind of country that obnoxious tin-pot dictator has been building. Recently, up until a month ago, even Putin was a strong, masculine, Christian role model for not a negligible portion of Republicans. And for the full Hungarian right-wing elite.

Brexit has been a great example of making a decision that had clear, numerous, and thoroughly explained drawbacks, mostly imaginary benefits, and was made in a fight against non-existing enemies. Trump is the best example of how people can descend into complete, bottomless madness.

Reality calls

Putin's attack on Ukraine was a jolt of common sense into the common consciousness. Life can be serious, and decisions have consequences. Reality doesn't care about your pet fantasies. Our brief, ahistorical era of complacency is over.

It won't wake up people who are already invested in their beliefs. Almost nothing does. But it will sway people who are sitting on the fence. Many liberals will realize that the West might be not the worst place to live, and who goes to what toilet might be not the most important problem of the world today. And some strongman-sympathizer Christian nationalists will sympathize less. On both sides, the taken-for-granted advantages of liberal democracies, like not being sent to Siberian prison camps for opposing the government, or beaten up by the police just for protesting against a war, will be a bit more appreciated.

Regardless of how individual thinking on these issues will change, the public tolerance for people whining about hurt feelings and the oppressive nature of Western democracies will sink. Same for public admiration of "strong Christian leaders" (aka Putin&Orban).

The hardcore won't change, but as we finally have real problems to talk about, they will get less oxygen in public discourse. That's a good start.